(download as PDF)

FAQ on Controlled Digital Lending (CDL)

-

1. What is Controlled Digital Lending (CDL)?

-

Controlled Digital Lending (CDL) is a label coined by the Internet Archive and some lawyers and librarians to describe a particular methodology of digital piracy (unlicensed copying and distribution) of books. Earlier, and more accurately, the Internet Archive described this as a process to “digitize and re-publish” books.1 In September 2018, the Internet Archive and some of its allies released a statement and white paper describing and defending this practice.2

-

2. How does CDL work?

-

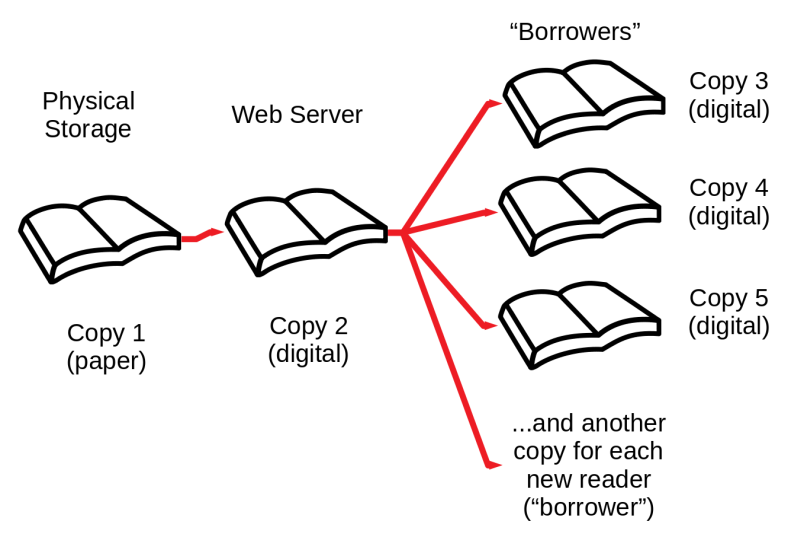

A library, archive, or other organization legally obtains a printed copy of a book, either by buying a copy or by being given a used copy as a donation. Next the library (or a “partner” such as the Internet Archive, or a contractor) scans the book to create a digital copy. Then that digital copy is uploaded to a Web server, and used to make another digital copy for each reader:

-

3. What’s wrong with this? Why is it a problem? Why should I care?

-

CDL infringes authors’ and publishers’ copyrights and deprives them of revenues that they would earn if readers obtained their works though other, legitimate channels.

Libraries purchase licenses for legal “e-lending,” and authors normally receive a share of these licensing revenues, just as they do from sales of printed books. The prices for these licenses, and the terms for “e-lending,” are set by publishers and/or authors. Typically, these licenses require libraries to use specified technical means to ensure that a library can only lend a digital copy out to one person at a time, and that the copy distributed to a reader cannot be accessed after the loan expires.

As discussed in more detail below, CDL is not authorized by authors or publishers. Authors and publishers are paid nothing for the digital copies that are made and distributed on the basis of the theory of CDL. These copies include Web pages of scanned images of books that can be saved, printed, or read indefinitely, even after they are marked as “returned.”

Digital copies have different uses from physical copies. They are not “equivalent,” and they typically have different prices and terms of sale or licensing. And while proponents of CDL argue that they are “substituting” a digital copy for a physical copy that they own, they actually retain the original printed copy as well as making and distributing an unlimited number of digital copies.

-

4. Who is doing this and promoting this?

-

The practice of CDL was pioneered by the Internet Archive through its OpenLibrary.org website.3 It is being promoted to, and beginning to be practiced by, libraries and archives throughout the U.S. and in other countries.4

-

5. How long has this been going on?

-

We don’t know for sure, since the Internet Archive didn’t ask us for permission or tell us when it started scanning and distributing digital copies of our books. But the Internet Archive now says that it has been doing this with current, in-print, in-copyright books since at least 2010.5

-

6. How many books have been scanned and are being distributed?

-

“The Internet Archive currently digitizes approximately 1,000 books per workday (250,000 per year)”6 In October 2016 the Internet Archive said that “more than 500,000” in-copyright books had been scanned and were being distributed online.7 In 2017 the Internet Archive applied for a grant to “digitize and re-publish approximately 3-4 million books at Internet Archive-run facilities in the United States, Hong Kong, [and] Shenzhen, China.”8 In October 2018, after that grant application had been rejected, the Internet Archive still described its OpenLibrary.org program as “A visionary project to digitize and lend 4 million… books.”9

-

7. Has anyone objected to this?

-

Yes. Many authors have no idea that books they have written, or in which their writing or imagery is included, have been scanned and are being distributed in digital form by the Internet Archive. But of those authors who have found out that their work is included, many have objected.

The Internet Archive responded to some of these initial individual objections by stopping distribution of new copies of these books on OpenLibrary.org.

Since the release of its statement and white paper on CDL, the Internet Archive has refused to honor some takedown requests related to books on OpenLibrary.org, and has defended its continued distribution of unauthorized copies of these works on the basis of the CDL theory. The Internet Archive has not yet been willing to compensate authors or to discuss writers’ objections to the legality of CDL.

No organizations of working authors were invited to the events at which the Internet Archive and its allies have evangelized the concept of CDL to other librarians and archivists, so many librarians and archivists are unaware of the basis or extent of authors’ objections to CDL which have led to the issuance of the “Appeal from the Victims of Controlled Digital Lending.”

-

8. What about DMCA takedown requests?

-

Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) takedown notices are used to object to content posted by “users” of platforms and hosting companies. In the case of CDL, the Internet Archive and its partners post the content themselves and so are directly responsible for the copying, distribution, and copyright infringement. The Internet Archive is not entitled to DMCA “safe harbor” protection for copies it has created itself and posted to OpenLibrary.org or otherwise on its own websites, and so DMCA takedown procedures do not apply to these files.

The Internet Archive also hosts copies of books on Archive.org that have been uploaded by Archive.org users, including amateur scans and pirate copies of some of the same books. These are subject to DMCA takedown procedures. But these are not the books being distributed through OpenLibrary.org or on the basis of the CDL theory. The Internet Archive has not published any takedown policies or procedures for books being distributed through OpenLibrary.org or on the basis of the theory of CDL.

-

9. Has anyone sued the Internet Archive or libraries for CDL copying?

-

Not yet. Even simple copyright lawsuits must be brought in federal court, and often cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. A challenge to the Internet Archive could easily cost millions. The legal system favors entities with deep pockets over individuals. Universities have lawyers, including law professors, available on staff or pro bono to defend them, and have legal resources orders of magnitude greater than those of individual authors. Authors have to pay for our own lawyers, and can rarely afford to take even the most flagrant copyright thieves to court. Lack of lawsuits for copyright infringement against the Internet Archive or its partners in CDL should not be taken as acceptance of their legal claims or lack of outrage at their actions.

-

10. What types of books are being copied and distributed?

-

All kinds of books: fiction, non-fiction, textbooks, children’s books, novels, anthologies, poetry, plays, cookbooks, guidebooks, reference books, illustrated books, art books, photography books, etc.10 The Internet Archive solicits donations of books of any type and appears to scan and distribute whatever it gets.11

-

11. Are these books all old enough to be in the public domain?

- No. Most of them are recent enough to still be in copyright. The Internet Archive says that the largest number of books available through OpenLibrary.org by decade of publication were published in the 1990s.12

-

12. Are these books all out of print?

-

No. Many of them are in print and listed in “Books In Print” and other similar catalogs.

-

13. Are some of the works in these books “orphan works”?

-

Very few of the works in the books that the Internet Archive has scanned and is distributing through CDL are likely to be “orphan works.” But so what if some of them are?

So-called “orphan works” have been defined – by those who want to copy these works without permission – as works to which the holders of certain rights cannot be identified or found. CDL proponents and other promoters of free copying of books greatly exaggerate the problem of orphan works. Because of the ways books are published, the text of a published book is among the types of written works least likely to constitute orphan works. The Authors Registry has been able to identify rightsholders of 90% of a sample of books claimed to contain “orphan works,” even including out-of-print books, in less than 30 minutes per book. Of the remainder, some may contain true orphan works (most often because the rights in question were held by a publisher that has gone out of business), but the numbers may be small.

Moreover, whether a rightsholder can be identified or found says nothing about whether the work is available to readers or is generating revenue for the author. Some orphan works are being actively exploited, and orphan works are the primary source of income for some authors.

Nothing in the definition of an “orphan work” implies that such a work is not being commercially exploited or that copying it will not interfere with the author’s livelihood.

Anonymously self-published websites, for example, are by definition orphan works, regardless of how much revenue they are generating. Authors of these works include, among others, writers on controversial or stigmatized subjects, whistleblowers, muckrakers, and writers who fear retaliation if they were identified or found. Monetization through advertising does not require any transaction between the reader and the author or rightsholder, and does not require the reader to be able to identify, locate, or contact the author or rightsholder. A work is also, by definition, an orphan work if a contract assigning all rights to the work – for which the author was paid, and/or is receiving continuing payments – contains a nondisclosure agreement that forbids the author from disclosing to whom the exclusive rights have been assigned.

-

14. Is CDL happening only in the USA?

-

No.The Internet Archive is already scanning books from Canadian libraries, and has scanned and is distributing copies of books published around the world in many languages.13

-

15. Is CDL authorized or approved by authors or publishers?

-

No. Some of the books available in digital formats from OpenLibrary.org are being distributed under licenses or by permission of publishers and/or authors. Others are older works that are in the public domain. But these aren’t the books being distributed under the theory of CDL. The Internet Archive has neither asked for, nor received, permission to copy any of the works in books distributed under the theory of CDL through OpenLibrary.org, Archive.org, or other websites.

-

16. If I browse the Internet Archive catalog, can I tell which e-books are licensed and which are unauthorized digital bootlegs?

-

No. The Internet Archive catalog doesn’t show which e-books it has licensed and which it has copied and is distributing on the basis of CDL or on some other basis. The only way to tell is to ask the author(s) if they have authorized the Internet Archive to distribute a digital edition.

-

17. Do libraries buy or license the digital copies they distribute through CDL schemes?

-

No. They start with a legally acquired printed copy, but for the books being distributed under the theory of CDL, all of the digital copies made and distributed are unauthorized. No payment is made to the authors or publishers for any of the digital copies made on the basis of CDL.

-

18. How is CDL different from what libraries do when they “lend” e-books licensed from publishers or authors?

-

Libraries pay for licenses to e-books that they “lend,” separately from purchases of physical books.

Because library e-book “lending” actually involves copying onto the reader’s device, it requires a separate license, for which publishers or authors are entitled to set a separate price. The right to set pricing and licensing terms is among the most important elements of copyright.

Publishers or authors who set prices and licensing terms generally charge more for these “e-lending” licenses than for copies of printed books or for single-user e-book licenses, or keep the terms of e-lending licenses shorter than those of retail e-book licenses, because library e-books are easier for users to access and so can dampen the market for individual sales or licenses more than physical library books that require a visit to the library. If an e-book licensed for e-lending is worth more and can be read by more people (since it never wears out) than a printed book, a publisher or author can charge more for it.

-

19. Isn’t a digital copy the same as a paper copy?

-

No. They are different and are priced differently. Paper copies are subject to damage and loss, and can only be read a limited number of times before they wear out. More durable hardcover editions cost more than short-lived paperbacks, but still don’t last forever. A license in perpetuity for a digital copy is more valuable than, and typically costs more than, a paper copy.

-

20. Does possession of a paper copy imply the legal right to make a digital copy?

-

No. Possession of a copy doesn’t imply the right to make additional copies in any format. Courts – including the U.S. Supreme Court in its decision in New York Times v. Tasini14, a case which involved the digital use of work first published in print – have consistently recognized that the right to make paper copies and the right to make digital copies are distinct rights, and that a license for print copying does not imply a license for digital copying.

Lending of legally acquired physical books does involve the right of “distribution,” which is one of the bundle of rights that make up “copyright.” But the transfer or loan of a physical copy is specifically allowed under the “first sale” (or “exhaustion”) doctrine, an exception to the right of distribution. That “first sale” doctrine for transfers or loans (without copying) of physical books does not create a right to make new physical or digital copies, as was found most recently in Capitol Records v. ReDigi, 16-2321 (2nd Circuit, December 12, 2018).

-

21. Didn’t the courts approve this sort of copying in the “Google Books” cases?

-

No. A key factor in the courts’ approval of Google’s book-scanning was that Google only distributes “snippets” (excerpts) of scanned books.15 CDL, as described and as practiced by the Internet Archive, involves distribution of complete images of every page of a scanned book.

-

22. Is CDL really “controlled lending”?

-

No, it is neither “controlled” nor “lending,” as explained below. It’s a scheme for the production and distribution of inferior, unauthorized bootleg e-book editions of printed books.

-

23. Is CDL comparable to what libraries do when they lend printed books?

-

No. Library lending of printed books, CDs, DVDs, or other tangible objects is different from lending electronic copies because lending the physical objects does not involve copying. When a library lends a printed book, it lends the same copy it purchased. It lends the same copy to each borrower in succession. It can’t lend that copy to anyone else until it is returned. If that original copy wears out or is lost, the library can’t lend it again unless and until it buys another copy. CDL is fundamentally a copying scheme, which involves making a digital copy from a paper copy, uploading that digital copy to a Web server, and then making an additional digital copy to send to each “borrower.”

“Lending” of e-books is also very different from lending of physical copies in its effect on sales or licensing of individual copies. Because digital copies are so much more easily and quickly accessible, without having to go to a library, lending of digital copies via the Web is more likely to replace sales or licenses of e-books than is availability of physical books in a library to replace sales of those books. Anyone can “borrow” an e-book from their desktop, laptop, or smartphone, at any time of day, and from a variety of libraries. Some so-called “libraries” are open to the entire world, and sophisticated online readers know how to borrow e-books from just about any library. A physical copy of a book, held in a single location, has much less affect on the markets for the works in that book than a digital copy instantly accessible worldwide.

-

24. How many copies are made of each book “loaned” through CDL?

-

An unlimited number. An additional digital copy is made and sent to each “borrower.”

-

25. Does the digital copy “loaned” through CDL have to be returned before another reader can receive a copy?

-

No. Web servers and Web browsers don’t work that way. There’s no technical means by which a Web browser can return a file to the Web server, or that the server can force the browser to delete an image or other file from its cache. The Internet Archive allows CDL e-books to be downloaded as PDF files or viewed in a Web browser as full-page images. The Internet Archive says that an e-book must be “returned” before another copy will be sent to another reader. That means that either the reader clicks on “return” in their browser (which doesn’t actually “return” the page images or PDF file to the server or delete them from the browser cache), or two weeks pass. After two weeks, the Internet Archive deems the book “returned,” regardless of whether the “borrower” has clicked on “return” or still has copies of the files.16

-

26. Can only one person at a time read a book “loaned” through CDL?

-

No. Any number of people who have received copies of a book can be reading them simultaneously. Even after a CDL e-book is “returned,” the page images remain in the browser cache and can still be viewed, printed, saved, or copied, with no technical controls or restrictions.

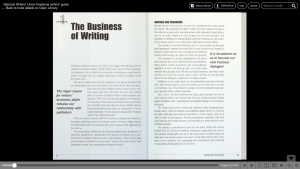

Here’s an image of two pages from the Freelance Writers’ Guide published by the National Writers Union (NWU), downloaded from the Internet Archive under CDL. The Internet Archive shows this e-book as “returned” and available to the next “borrower.” But like all of the previous “borrowers,” we were able to keep copies of complete images of all of the pages, which we can still read, copy, and print:

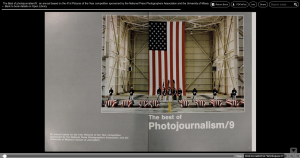

Books containing primarily photographs and illustrations rather than primarily text are also being distributed under the theory of CDL. Here’s a spread from one of the annual volumes of award-winning photographs published by the National News Photographers Association (NPPA), also retained in the browser cache after the book was marked as “returned” on OpenLibrary.org:

-

27. Is CDL legal or is it copyright infringement?

-

CDL is not legal. It’s copyright infringement. Unlike lending of physical books, CDL requires copying. And that copying is copyright infringement unless it is authorized either by the copyright holder or by one of the exceptions or limitations in copyright law. CDL is not.

-

28. Is CDL allowed as a “fair use” under U.S. copyright law? Is CDL allowed by the Berne Convention and other international copyright treaties?

-

No. The test for “fair use” under U.S. law and the test for permissible exceptions to copyright in the Berne Convention include similar requirements which are not met by CDL:

“In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include — … (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.”17

“It shall be a matter for legislation … to permit the reproduction of such works in certain special cases, provided that such reproduction does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author.”18

In order to assess whether a use is fair use, someone must first assess “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work” and whether it would “conflict with a normal exploitation of the work.”

These are factual questions. Even the best lawyer can’t determine whether copying is “fair use” or whether an exception or limitation to copyright to permit copying in a particular situation would be permitted by the Berne Convention “three-step test,” without fact-finding about how writers normally “exploit” (earn money from) these works, and what are the potential markets for these works.

Neither the Internet Archive nor the authors of the statement and white paper on Controlled Digital Lending have asked working writers how we earn money from our works that are included in the books that they and their colleagues and institutions are scanning and distributing, or what the potential markets are for those works.

It’s no surprise that, in their ignorance, they rely on completely mistaken assumptions.

According to the Position Statement on Controlled Digital Lending, “The final fair use factor looks at the market effect of the secondary use. For CDL, the arguable negative impact is the loss of sales [of books] due to lending as a substitution.”19 The White Paper on Controlled Digital Lending of Library Books says that “For the 20th Century books which make up the bulk of materials that would benefit from CDL, there is not a functioning market in place to be harmed” because “20th century books … are generally not available in digital formats.”20

The Position Statement and White Paper on CDL mistakenly consider only the market for books, rather than the many markets for works that have been included in books. Sales of books are not the only way authors exploit works included in books, or the only current or potential market for works included in books. The “new normal” of writers’ revenues is much broader. Most writers need multiple revenue streams to try to make a living, and different writers have different revenues sources of which even their fellow writers may be unaware.

There’s no reason for lawyers or librarians to expect that they would be familiar with how various types of working writers, photographers, and artists earn our livelihoods. Many of the ways authors make money from our works are not obvious to librarians. There’s no way anyone can tell, just by looking at a book or the listing for it in a library catalog, whether the works included in that book are available in digital formats, or what other ways those works are generating income for the authors. A good-faith fair-use analysis should begin with a good-faith consultation with diverse working authors of the types of works that are to be copied.

-

29. Do supporters of CDL have a basis for a good-faith belief that it is legal?

-

No. The prerequisite to applying the legal test for “fair use” is fact-finding as to the normal exploitation and potential markets for these works. Someone who has not made a good-faith fact-finding effort to ask working authors how we normally exploit works included in books, and what are the potential markets for those works, cannot plausibly claim to be prepared to apply those legal tests, or to have a good-faith belief that CDL passes those legal tests. Failure to carry out this fact-finding consultation with working authors is evidence of bad faith.

-

30. How are writers, photographers, and graphic artists earning money from works included in out-of-print books? What are the potential markets for these works?

-

More and more ways to monetize written and graphic works are becoming the new normal. Here’s a non-exhaustive list of some of the first ones that come to mind:

-

- (a) Sales of physical books (including sales of the original print edition and sales of new self-published and other print and print-on-demand editions)

- (b) Licensing of e-books (including new and self-published e-book editions), directly to readers or through a publisher, distributor, or other platform

- (c) Licensing of audio books (including new and self-published editions), directly to readers or through a publisher, distributor, or other platform

- (d) Licensing of enhanced or multimedia e-books (including new and self-published editions), directly to readers or through a publisher, distributor, or other platform

- (e) Licensing of stories, articles, excerpts, poems, photos, illustrations, etc. for inclusion in new print and digital anthologies

- (f) Licensing of stories, articles, excerpts, poems, photos, illustrations, etc. for classroom or corporate distribution

- (g) Licensing of stories, articles, excerpts, poems, photos, illustrations, etc. for inclusion in print and digital periodicals

- (h) Licensing of stories, articles, excerpts, poems, photos, illustrations, etc. for inclusion in Web content (for a one-time fee, a periodic license fee, or a share of ad revenue)

- (i) Licensing of stories, articles, excerpts, poems, photos, illustrations, etc. for inclusion in e-mail newsletters

- (j) Licensing of stories, articles, excerpts, poems, photos, illustrations, etc. for inclusion in mobile apps (e.g., excerpts from a cookbook or guidebook in a recipe or travel app)

- (k) Licensing of stories, articles, excerpts, poems, photos, illustrations, etc. for use in electronic games or virtual reality experiences (e.g., as the plot, the basis for characters, or part of the graphics)

- (l) Per-download or subscription fees for digital “offprints” and excerpts

- (m) Self-published Web content that generates advertising, subscription, or other revenue

- (n) Mobile apps that generate revenue through app licenses, in-app advertising, etc.

- (o) E-mail newsletters that generate revenue through subscriptions, advertising, etc.

- (p) Subscriptions to Kindle Unlimited or other “Netflix for e-books” services

- (q) Licensing of written or visual works for use in corporate communications

- (r) Licensing of works of visual art (photographs, illustrations, graphic art) for use on commercial products

- (s) Licensing through syndication services, stock photo agencies, etc.

- (t) Collective licensing of secondary rights by Reproduction Rights Organizations.21

Some of these publication formats have no ISBNSs, don’t appear in library collections, catalogs or bibliographic databases and are wholly or largely “off the radar” to librarians. Only the first of these revenue sources is even partially considered by the authors of the White Paper on Controlled Digital Lending. But the making and distribution of new digital copies under the theory of CDL can divert readers and undermine revenues from all these authorized editions and formats in which works included in out-of-print books can be included.

-

-

31. Are these revenues and potential markets from works included in out-of-print books significant for writers, photographers, and graphic artists?

-

Yes, for many writers and authors, and increasingly so.

The author’s royalty for a traditionally published book is typically only 5-15% of the sale price of a new printed book, while the author is typically entitled to 50-100% of the revenues for “secondary” uses of the works included in that book once it is out of print. As a result of this difference in the division of revenues, writers often earn more for each retail license of a self-published new e-book edition of a book that is out-of-print in the original edition, or even for a download of a single chapter or excerpt, than they received for each sale of the original book.

The fee paid for the use of a story, article, photograph, or illustration in a single book is often based in part on the number of copies of the book authorized to be printed, and is often only a small fraction of the value or total revenues for the work over the life of the copyright.

“Secondary” and backlist rights are now the primary sources of income for many writers, photographers, and artists, often making a substantial contribution to the incomes of many others. Written works find new audiences and markets. Works of visual art – illustrations, designs, and photography – are often licensed for new uses, such as commercial products, as new markets are reached and as the imagery becomes in vogue.

-

32. How are writers and authors harmed by Controlled Digital Lending?

-

If a reader can get a work (or the portion they want to read or view) online, for free, from the Internet Archive at OpenLibrary.org, they are likely to do so rather than to seek out any other version of the work. CDL diverts readers and potential revenues from all other editions, versions, formats, and channels through which the author might be making all or parts of the same work available.

As discussed further below, diversion of readers to CDL copies distributed from the U.S. by the Internet Archive or other U.S. institutions also deprives authors of the Public Lending Right (PLR) payments they would receive for borrowing of books from foreign libraries.

Authors are also harmed by the loss of control over whether new copies of a work are made, which version of a work is copied, or in what form or format the work is copied.

An author may prefer not to license any more copying of a work that no longer reflects their views, or that they don’t think enhances the value of their personal brand. An author may prefer that only a particular version of a work (such as a revised or updated version) be copied, in preference to other versions. An author may choose to authorize copying only in a certain form or format, and not in other formats that they think don’t show the work the way they want. The right to make these choices about new copying is part of the author’s copyright. Anyone can read the existing copies, but that doesn’t mean that they can make new copies without permission.

-

33. How are readers harmed by Controlled Digital Lending?

-

If CDL diverts readers from legitimate digital editions and deprives authors of income, fewer writers will be able to devote their time to writing. For the works that are included in CDL, blurry scanned images or error-filled OCR text are far inferior to proper digital editions, which are less likely to be made available if the market has already been preempted by CDL bootlegs.

-

34. Are the works in these books already available in other digital formats?

-

Sometimes, yes. Some of these works are available in standard e-book formats. Much larger numbers are available in other digital formats, as discussed above, which don’t qualify for ISBNs. If the URLs or other information about these other forms and formats aren’t listed in library catalogs, that’s because librarians have refused to allow us to add this information to those catalogs.

Neither the Internet Archive nor its “partner” libraries have asked authors, before scanning our books, whether our works were already available in other digital formats.

-

35. Are there other ways to make works that were published in out-of-print books available in digital formats?

-

Yes, absolutely. Of those writers who haven’t already made their personal backlists available in any digital form, a large proportion would be happy to give librarians permission to digitize their work, if libraries made them a licensing offer on reasonable terms. Most writers would rather work with libraries and librarians than with Amazon or other intermediaries.

-

36. Do writers want all our previously published works made available in digital forms?

-

We cannot speak for all writers, but many would like to have their books available in digital form. There are cases, however when a writer doesn’t want new copies made of some portion or all of their previously published work. In such cases, (a) it’s their legal and moral right to make that decision, and (b) there’s usually a good reason, such as that the work or version no longer reflects their views; that they would rather have any new copying be of a revised, updated, or improved version; or that they have already – for an agreed price, typically one much higher than the price of a non-exclusive license – sold someone else an exclusive license to copying or use of the work.

-

37. Do writers support digital libraries?

-

Yes, absolutely. Working freelance writers who own the rights to our personal backlists, and depend on them for continuing income if we are to be able to retire, have more of an interest than anyone else in making and keeping our out-of-print work available. Nobody has done more to re-issue out-of-print books, and works that were included in them, in new digital editions and formats, than authors ourselves. Libraries and librarians should want to work with us and not try to undermine our ability to earn enough money to finance these new digital editions.

-

38. Should authors get paid when our work is copied?

-

Of course. This is the heart of our objection to CDL: Everyone is getting paid, except the writers, photographers, illustrators, and graphic artists who created the works that are being copied and distributed. The librarians are getting paid. The scanner operators are getting paid. The programmers are getting paid. The builders of the server farms are getting paid. The system administrators are getting paid. The authors, and only the authors, are getting nothing.

-

39.Should authors be paid when our works are borrowed from libraries?

-

Yes, in the opinion of many authors and authors’ organizations.

This may still be a little-known or controversial idea in the U.S., but recognition of a Public Lending Right (PLR) to remuneration of authors for library lending is increasingly the international norm.22 It’s already the law in Canada, the U.K., Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, throughout the European Union, and in a growing number of other countries.23

Our objections to CDL don’t depend on recognition of PLR in the U.S. But in addition to its other harms, CDL deprives authors of PLR compensation by diverting readers who would otherwise borrow books from foreign libraries to “borrow” bootleg CDL copies served up from the U.S. by the Internet Archive or other U.S. institutions.

-

40. What can librarians do if they want to help writers as well as readers?

-

First, talk to working authors. We appeal for a dialogue on e-book lending and digital rights to backlist and out-of-print works among working writers, photographers, graphic artists, librarians, and archivists, and for inclusion of working authors in fair use assessments.

Librarians should not assume that new modes of exploitation of written work, or new formats, distribution channels, and business models, will “automagically” be visible to libraries.

There’s been some dialogue between book publishers and librarians about e-books, but little comparable dialogue with working authors. Publishers are not proxies for authors’ interests.

Librarians need to recognize the increasing disintermediation of traditional publishers and engage directly with working writers if they want their catalogs and collections to reflect the diversity of new formats and business models for distribution of written work.

Second, open your catalogs and bibliographic databases to crowd-sourcing and input from authors. We understand that librarians fear that crowd-sourcing of catalog data would entail a loss of control. But much of the information about where and how the works library patrons want to read, including works in out-of-print books, are already available in digital formats can be obtained only from authors. Keeping the doors to your catalogs and databases closed to data crowd-sourced from authors will only continue to deprive library patrons of useful information and drive librarians to copyright-infringing tactics such as CDL, when the works you want to copy may already be available for access or licensing.

As one example of how this might work, writers would be able to add pointers to library catalog records for out-of-print books to indicate the URLs where, or distributors or services through which, new versions of those books, or portions of them, are available.

Many writers want to make their out-of-print works available, and would rather spend time writing new work than self-publishing their personal backlists. Make it easy for the author of any printed book in your collection to give you permission to scan and distribute the book in digital form, for free or for a fee, or using standard licensing terms. One of the bad-faith aspects of CDL is that our work is being scanned and redistributed, on the basis of a false claim that there is no other way to make it available, without first giving us a chance to give permission.

Third, support legislation to make it easier for authors to recover rights to our work, especially when – as is common – the original publisher is out of business. Once we reclaim our rights, working authors have every interest in making our backlist works available, or licensing them to others to do so. Librarians who want us to be able to make our work available should endorse the calls by organizations of authors for reform of Section 203 of the Copyright Act (17 U.S. Code § 203).24

Fourth, support legislation to establish a Public Lending Right (PLR) in the USA.25 Diverting readers from foreign libraries in countries which recognize PLR to digital copies delivered online from U.S. libraries or servers would be less damaging to authors if the U.S. also provided remuneration of authors when books or e-books are borrowed from libraries.

Signed:

- National Writers Union (UAW Local 1981, AFL-CIO)

- Novelists, Inc.

- Authors Guild

- American Society of Journalists and Authors (ASJA)

- Textbook & Academic Authors Association (TAA)

- National Association of Science Writers (NASW)

- Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI)

- Graphic Artists Guild

- American Society of Media Photographers (ASMP)

- National Press Photographers Association (NPPA)

- American Society for Collective Rights Licensing (ASCRL)

- American Photographic Artists (APA)

- Songwriters Guild of America (SGA)

- The Writers Union of Canada (TWUC)

- Union des écrivaines et des écrivains québécois (UNEQ)

- Professional Association of Canadian Literary Agents (PACLA)

- Association nationale des éditeurs de livres (ANEL)

- Copibec

- Society of Authors

- Association of Authors’ Agents (AAA)

- Sanasto

- International Authors Forum (IAF)

- International Federation of Journalists (IFJ)

- European Federation of Journalists (EFJ)

- European Writers’ Council (EWC)

- European Visual Artists (EVA)

- Mystery Writers of America (MWA)

- Canadian Authors Association (CAA)

- Romance Writers of America (RWA)

Footnotes:

1. Internet Archive Open Libraries Proposal, MacArthur Foundation 100&Change, July 13, 2017, <https://archive.org/details/OpenLibrariesNarrative>.

2. “Controlled Digital Lending”, <https://controlleddigitallending.org/>.

3. See <https://archive.org/details/inlibrary> and <https://openlibrary.org/>.

4. See <http://openlibraries.online/> and <http://www.libraryleadersforum.org/>.

5. “Since 2010, the Internet Archive’s OpenLibrary.org site has been piloting collaborative collection and lending of 20th-century books contributed by dozens of libraries. For six years, we have been… digitizing physical books to lend.” Brewster Kahle, Transforming Our Libraries into Digital Libraries: A digital book for every physical book in our libraries, (Whitepaper for the Library Leaders Forum held at the Internet Archive in October 2016), <https://archive.org/details/TransformingourLibrariesintoDigitalLibraries102016>.

6. Internet Archive Open Libraries Proposal, MacArthur Foundation 100&Change, July 13, 2017, <https://archive.org/details/OpenLibrariesNarrative>.

7. “We now lend more than 500,000 post-1923 digital volumes… via the Open Library website.” Kahle, Transforming Our Libraries into Digital Libraries, 2016.

8. Internet Archive Open Libraries Proposal, MacArthur Foundation 100&Change, July 13, 2017, <https://archive.org/details/OpenLibrariesNarrative>.

9. “Open Libraries Forum 2018 — October 18: Building Open Libraries”. <http://www.libraryleadersforum.org/> (visited December 10, 2018).

10. See the non-exclusive top menu bar of categories at <https://openlibrary.org/>.

11. “The Internet Archive has been scanning books for some years now, and we’re always looking for more…. Please help us by donating books to be scanned…. How Does The Book Drive Work? You can simply send books or drop them off in person at our headquarters…. Have a big donation? Please call us.” <https://openlibrary.org/bookdrive>

12. Lila Bailey (Policy Counsel, Internet Archive), slides from presentation, “Controlled Digital Lending (CDL): A Panel to Discuss Legal and Practical Considerations Involved in the Implementation of CDL by Public and Post-Secondary Libraries in Canada”, ABC Copyright Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, May 31, 2018, available at <http://summit.sfu.ca/system/files/iritems1/18093/CDL%20Panel%20-%20ABC%20Copyright.pdf>.

13. “Over the last five years, the Internet Archive has digitized and lent modern materials originating from the Boston Public Library, University of Toronto, and many other libraries.” Brief of amici curiae American Library Association, Association of College and Research Libraries, Association of Research Libraries, and Internet Archive in support of reversal, Capitol Records, LLC, v. Redigi, Inc., 16-2321-cv, 9th Cir., February 14, 2017, available at <https://www.librarycopyrightalliance.org/storage/documents/ReDigiFairUse_2017feb14-rs.pdf>. See also the statement in opposition by the Union des écrivaines et des écrivains québécois (UNEQ), «Make Canadian Libraries Great Again!» ou comment exploiter les failles de la Loi sur le droit d’auteur, December 3,2018, <https://www.uneq.qc.ca/2018/12/03/comment-exploiter-les-failles-du-droit-dauteur/>.

14. 533 U.S. 483 (2001)

15. Authors Guild v. HathiTrust, 755 F.3d 87 (2d Circuit, 2014), Authors Guild v. Google, 804 F.3d 202 (2nd Circuit, 2015)

16. That what was described as a “sale” actually involved copying, and that copies of a file could be retained after it was “sold”, were key factors in the finding of copyright infringement in Capitol Records v. ReDigi, 16-2321 (2nd Circuit, December 12, 2018).

17. U.S. Copyright Act, 17 U.S. Code § 107

18. Berne Convention on Copyright, Article 9

19. <https://controlleddigitallending.org/statement>

20. <https://controlleddigitallending.org/whitepaper>

21. Such as members of the International Federation of Reproduction Rights Organisations (IFRRO), <https://ifrro.org>.

22. See Public Lending Right (PLR) International, <https://plrinternational.com/>.

23. Dr. Jim Parker, “The public lending right and what it does”, WIPO Magazine, June 2018, <https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2018/03/article_0007.html>.

24. National Writers Union Priorities for Copyright Reform, adopted by the NWU Delegate Assembly, August 2013, available at <https://nwu.org/book-division/position-papers-and-resources/priorities-for-copyright-reform/>; Authors Guild Legislative Priorities, 116th Congress, available at <https://www.authorsguild.org/2019priorities>.

25. From the President, James Gleick, The Authors Guild, <https://www.authorsguild.org/PLRletter>; resolution by the National Executive Committee of the National Writers Union, September 2017, available at <https://nwu.org/nwu-endorses-u-s-copyright-reform-bills/>.

NWU is the sole provider of IFJ Press Passes to freelance journalists in the U.S.

NWU is the sole provider of IFJ Press Passes to freelance journalists in the U.S.