The NWU presented a public informational webinar on “What is the Internet Archive doing with our books?” on April 27 and May 5, 2020. The webinar explains “Controlled Digital Lending”, the “National Emergency Library”, and “One Web Page for Every Page of Every Book”:

Related articles:

- We Need Federal Funding for Distance Learning, During the Pandemic — and After

- Publishers Sue the Internet Archive for Scanning Books

A year ago, the NWU spoke out against the Internet Archive’s ongoing and expanding book scanning and e-book bootlegging practices. We joined dozens of national and international organizations and federations of authors (writers, photographers, illustrators, graphic artists, translators, etc.) and publishers from around the world in a joint Appeal to readers and librarians from the victims of Controlled Digital Lending. And we published a joint FAQ about Controlled Digital Lending, explaining what’s happening, how it harms authors, and why it is (and should remain) illegal.

But the Internet Archive’s book scanning and e-book bootlegging have never been limited to the practices its supporters have described as Controlled Digital Lending, or those it now describes as a National Emergency Library. The Internet Archive’s actual uses and re-distribution of unauthorized copies of images (and audio generated from them) of pages scanned from books are, and have long been, more extensive, less controlled and more damaging to authors’ incomes.

Now that the debate has moved beyond Controlled Digital Lending, we’re providing some additional answers to Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the multiple ways the Internet Archive is distributing images of pages scanned from printed books. These include, but are not limited to, what the Internet Archive has described as “Controlled Digital Lending”, the “National Emergency Library”, and “One Web Page for Every Page of Every Book”.

We hope that this information will inform the discussion and debate; build awareness among authors about what the Internet Archive has been doing without consulting us; and perhaps help prompt the dialogue we have been pleading for with the Internet Archive, with its defenders, and–most importantly–with readers and librarians.

The Internet buys or legally acquires copies a copy of a printed book. But the Internet Archive has given itself (i.e. has taken) a series of progressive unpaid upgrades from each legal printed copy:

- Printed book

- Printed book + e-book (scanning)

- Printed book + e-book + audiobook (OCR, text-to-speech)

- Printed book + e-book + audiobook + “single-user” life-of-copyright e-book and audiobook e-lending license (“Controlled Digital Lending”)

- Printed book + e-book + audiobook + unlimited-users e-book and audiobook e-lending license (“National Emergency Library”)

Different editions in different formats are different products which can have different prices. There is often a higher price for a book + e-book bundle, for example, than for either a copy of the printed book or an e-book alone. But the Internet Archive pays for only the printed book and takes the whole bundle by making and distributing its own additional copies in all the other formats.

-

A. How does the Internet Archive distribute images of pages of the books it scans?

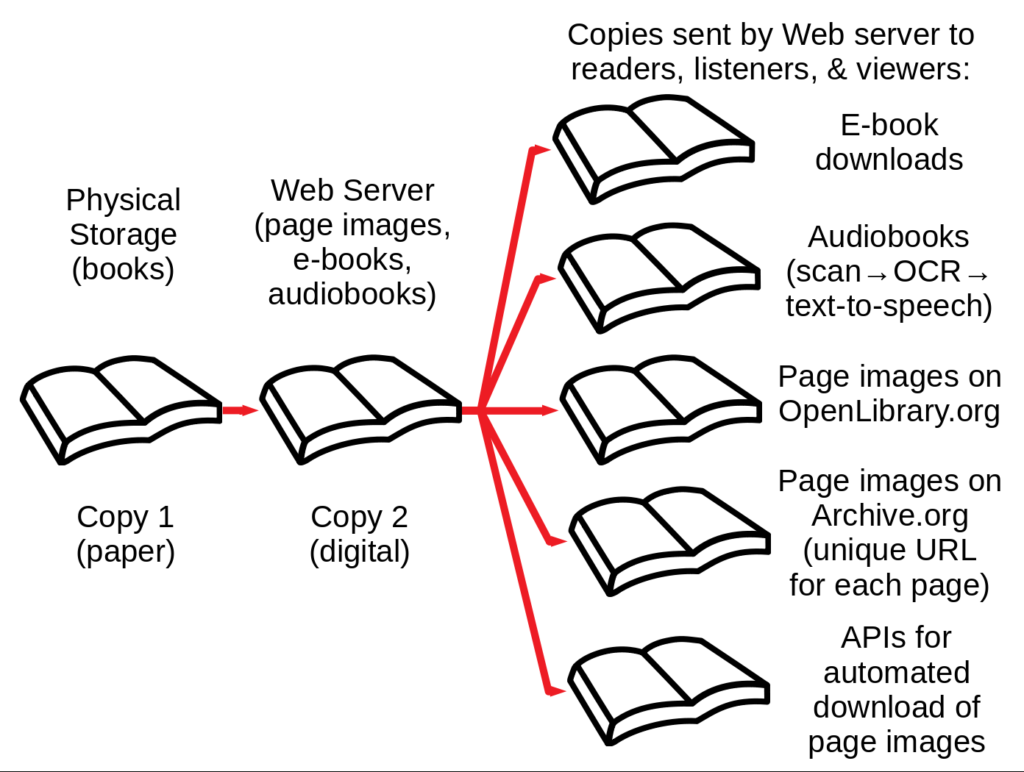

- The Internet Archive distributes images of or audio derived from each page of each of the books it scans in five ways, as shown in the diagram at the top of this article.

Only one of these modes of distribution fits the Internet Archive’s and its supporters’ description of so-called Controlled Digital Lending (CDL). Only one of these would correspond–if the Internet Archive paid for licenses, which it doesn’t–to what libraries do when they distribute authorized copies, pursuant to “e-lending” licenses.

Here’s how each of these five distribution channels works:

- Downloads via OpenLibrary.org of e-books assembled from page images

Most of the discussion of the Internet Archive’s book-scanning project and of the theory of so-called Controlled Digital Lending (CDL) has focused on downloads of e-books from the Internet Archive’s OpenLibrary.org website.

The Internet Archive describes this as “lending” or “borrowing” of “books.” But library lending of printed books doesn’t involve copying at all, and all of the copying involved in legitimate “e-lending” is specifically authorized by the terms of the license. The price reflects the copying rights granted.

A legitimate library either loans out the same printed copy it purchased, or purchases a license to distribute digital copies of an e-book in a manner specified by the license, but the Internet Archive does neither.

As explained in authors’ FAQ on Controlled Digital Lending, the Internet Archive legally acquires donated or discarded physical copies of books, but then illegally “re-publishes” them by scanning each page of each book to create a new, unauthorized digital copy in addition to its original printed copy.

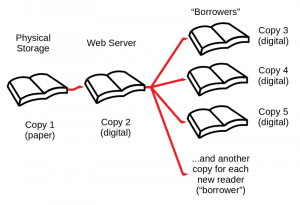

Then the Internet Archive assembles these page images into the master copy of a pirate e-book edition, and creates and sends an additional copy of this unauthorized e-book to each “borrower”:

This mode of distribution of unauthorized copies of images scanned from printed books corresponds, mostly, to what has been described as “Controlled Digital Lending” (CDL).

This mode of distribution of unauthorized copies of images scanned from printed books corresponds, mostly, to what has been described as “Controlled Digital Lending” (CDL).Downloads of the bootleg e-book files are available only to logged-in users of the Internet Archive. Anyone can register for free, including with a “throwaway” temporary email address. One user at a time is “authorized” by the Internet Archive to have a copy for 14 days at a time, in addition to the printed and digital copies retained by the Internet Archive. Digital rights management (DRM) software is used to try to enforce these limitations. But the Internet Archive has no authority to grant anyone else any rights in these works. For a subset of these e-books included in the National Emergency Library, any attempted limitation to one user at a time has been eliminated.

The illegality of this practice and the ways it harms authors are discussed in authors’ FAQ about CDL, the joint “Appeal to readers and librarians from the victims of Controlled Digital Lending,” and the NWU’s initial statement denouncing this practice and appealing for dialogue with readers and librarians.

Some defenders of CDL have claimed that our arguments against the legality of CDL also apply to legitimate library lending and “e-lending.” But that’s not true, because the legality of legitimate lending or “e-lending” depends on neither “fair use” nor market impacts. “Fair use” is a legal basis under US law for unauthorized copying under certain circumstances. “Fair use” requires taking into consideration the effects of the unauthorized copying on normal commercial exploitation of the works copied. Lending of printed copies doesn’t require any “fair use” analysis because it doesn’t involve copying at all. Licensed e-lending doesn’t require any “fair use” analysis because it involves only authorized copying.

When the Internet Archive says that it is doing “the same thing that libraries do with licensed e-lending”, it’s as if they snuck into a movie theater without paying, and then said, “But I was just doing the same thing that paying patrons do. Why are you complaining?” Libraries pay for licenses for the copying involved in “e-lending.” The Internet Archive makes copies similar to those made by licensed “e-lending” libraries, but without paying for a license to do so.

Copyright holders can take our assessment of likely market effects into consideration in pricing and setting licensing terms for authorized copying. We can’t do that with copies made without our permission on the basis of CDL, because the Internet Archive sets its own price (free) and its own terms for “re-publishing” our work.

- Audiobooks generated from images of scanned pages

After it assembles its scanned images of each page of a printed book into a bootleg e-book, the Internet Archive uses optical character recognition (OCR) software to generate a text file. Then it puts the text file through “text to speech” software to generate an audiobook in a synthesized voice.

The Internet Archive distributes some of these audiobooks only to registered users with credentials issued by the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled (NLS) of the Library of Congress. Many others of these files, however, are distributed to any registered OpenLibrary.org or Archive.org user. These OCR robo-reader audiobooks can be streamed directly from OpenLibrary.org or Archive.org.

Both an international treaty and US law create an exception to copyright allowing the creation of special editions for blind and print-disabled people, if and only if access is limited to eligible people. But the Internet Archive observes no such limitation: It distributes audiobooks and streams audio generated from OCR text to any registered user. The headphone icon for streaming audio is displayed and functional (next to the “borrow” button) for audio generated from many books regardless of whether a user has NLS credentials:

OCR-generated text is typically filled with errors, and a synthetic text-to-speech voice is a poor substitute for an expert human reader. But the Internet Archive disserves blind users by insisting on linking only to its own OCR-robo-reader audiobooks, even when authorized (and typically much more accurate, enjoyable, and useful) audio versions of books already exist. Even if there is a commercial audiobook version for all readers, or a quality noncommercial audio version for the blind and print-disabled from the NLS or Learning Ally (formerly “Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic”), the Internet Archive won’t mention it. Just as the Internet Archive won’t allow authors to add links on OpenLibrary.org or Archive.org to URLs where authorized editions or versions of works included in books are already available, even when existing authorized editions or versions are available for those works.

OCR-generated text is typically filled with errors, and a synthetic text-to-speech voice is a poor substitute for an expert human reader. But the Internet Archive disserves blind users by insisting on linking only to its own OCR-robo-reader audiobooks, even when authorized (and typically much more accurate, enjoyable, and useful) audio versions of books already exist. Even if there is a commercial audiobook version for all readers, or a quality noncommercial audio version for the blind and print-disabled from the NLS or Learning Ally (formerly “Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic”), the Internet Archive won’t mention it. Just as the Internet Archive won’t allow authors to add links on OpenLibrary.org or Archive.org to URLs where authorized editions or versions of works included in books are already available, even when existing authorized editions or versions are available for those works. - Viewing of page images on OpenLibrary.org

As was noted in our original author coalition FAQ about CDL, you don’t have to actually download encrypted e-books or install or use any DRM software to view the Internet Archive’s bootleg e-books. Once you have signed in and clicked on “borrow,” you can view any or all of the images of pages of the scanned book in your Web browser. We suspect that many more page views of book scans are distributed and viewed in this way, through Web browsers, than through downloads of e-book files.

The Internet Archive provides a viewer tool embedded in the webpage for each book. But the images of each page are actually downloaded by that tool to your local device for viewing, and stored as unencrypted JPG files in your browser cache folder.

There’s no attempt whatsoever to restrict how long any user retains these images, how they use them, or how many previous “borrowers” of the same book may actually have retained and be reading their copies simultaneously. Nor could there be any such controls on copies of images served up in this manner, given the way web servers and web browsers operate. As was also noted in the FAQ about CDL, the “Return” button on OpenLibrary.org doesn’t actually return or delete anything.

As should be obvious from this description, nothing about this mode of delivery of page images bears any resemblance to what has been described by supporters as “Controlled Digital Lending.” But in response to our initial FAQ on CDL, supporters of CDL and the Internet Archive released their own FAQ defending this practice of “in-browser viewing” of page images. It’s unclear–especially since the authors of the White Paper on CDL haven’t responded to our appeal for dialogue–whether they consider this to constitute a form of CDL (despite the absence of limitations on simultaneous readers or retention of copies), or whether they concede that it’s not CDL, but think it is legal on the basis of some other analysis.

Whether or not the Internet Archive or its defenders choose to define this practice as CDL (a term which is, of course, of their own invention), it’s part of what the Internet Archive is doing, and it fails the “fair use” test. It’s copyright infringement.

- Viewing of page images on Archive.org

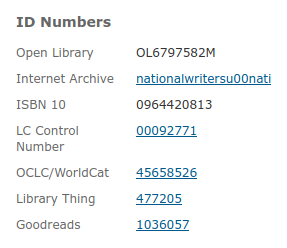

There’s a webpage for each scanned book on OpenLibrary.org. But there’s also a webpage for each scanned book, and a unique URL for each page of each scanned book, on Archive.org.

For example this page on OpenLibrary.org for one edition of the NWU’s Freelance Writers’ Guide includes a link, as shown in the screenshot below, to this page on Archive.org:

Images of each page of each scanned book can be viewed or downloaded from Archive.org, as from OpenLibrary.org, but with some significant differences between the functionality of the two sites: Archive.org doesn’t require a user account, sign-in, or “borrowing.” It doesn’t try to restrict the number of simultaneous downloads of each page. And it provides a unique, predictable, static, public URL for the unencrypted image of each page of each scanned book. These images are available on Archive.org regardless of whether the corresponding “ebook” is marked as “checked out” on OpenLibrary.org, belying any claim that there is any attempt to limit use or distribution of new copies to one copy or reader at a time.

Images of each page of each scanned book can be viewed or downloaded from Archive.org, as from OpenLibrary.org, but with some significant differences between the functionality of the two sites: Archive.org doesn’t require a user account, sign-in, or “borrowing.” It doesn’t try to restrict the number of simultaneous downloads of each page. And it provides a unique, predictable, static, public URL for the unencrypted image of each page of each scanned book. These images are available on Archive.org regardless of whether the corresponding “ebook” is marked as “checked out” on OpenLibrary.org, belying any claim that there is any attempt to limit use or distribution of new copies to one copy or reader at a time. For example, this URL, <https://archive.org/details/nationalwritersu00nati/page/52>, will take you directly to the scanned image of page 52 of the NWU’s Freelance Writers’ Guide:

[Update, April 16, 2020: Within hours after we posted this article, the Internet Article disabled the link we used as an example. We suspect they would disable any other specific link we substituted as an example. But you can try it yourself with any other book shown on OpenLibrary.org as available for “borrowing”, and see that you get to a page on Archive.org like the own shown in the screenshot above.]

If you get a message about “limited preview” rather than a display of the full page, clear the cookies in your Web browser, set your browser not to accept cookies, or open a new browser tab or window in “private” mode.” Unlike other book and e-book websites, Archive.org includes every page in its so-called “preview” of full-page images. There appears to be some rate limiting, and a limit on how many pages one user can download or view in one session, if your browser is set to accept cookies, before you have to clear the cookies. But if you clear cookies, you can download images of every page of a book simply by incrementing the page number at the end of the URL. Or you can use an API to automate the download process, as discussed below.

It’s unclear whether the unique URLs for individual pages were developed specifically for use by Wikipedia, or whether that’s just where they have found their greatest use. But it seems likely that the largest single source of traffic to the Internet Archive’s images of pages of scanned books is Wikipedia.org. Most of this traffic follows direct links from Wikipedia.org to scanned images of individual pages of books on Archive.org. It never goes through OpenLibrary.org or any of its “borrowing” mechanisms or DRM.

This isn’t an accident, a workaround, or some sort of “circumvention” of technical protections. It’s exactly how these links were intended and designed to work, as shown in this illustration from the Internet Archive blog:

A leaflet on “Citing Open Library on Wikipedia” distributed by the Internet Archive at a Wikipedia convention in 2014 described OpenLibrary.org as “One web page for every book.” But the example it gave was actually of a direct link to the scanned image on Archive.org of a specific page of a book:

A more accurate description of what the Internet Archive has created would be “One web page for every page of every book.”

A more accurate description of what the Internet Archive has created would be “One web page for every page of every book.”This is, we suspect the most commonly used method for obtaining the Internet Archive’s images of scanned book pages. It’s also the least controlled, the most obviously outside what has been described as CDL, the most flagrantly illegal, and the most damaging to many authors.

- APIs for automated downloads of page images

If you think it might be too tedious to click through every page of a book, the Internet Archive has anticipated your desires: There’s an application programming interface (API) for the Internet Archive. The Internet Archive’s API includes tools specifically for Open Library book scans that programmers can use to automate searches, discovery of URLs, and downloads of images of book pages.

These APIs have been used to build ‘bots to generate and insert links from Wikipedia pages to scanned images of book pages on Archive.org. But they can also be used to find, extract, and/or generate links to other works included in scanned books.

The types of works most likely to be contained, in their entirety, on one or two pages of a book are obviously graphic works. Poems, flash fiction, cooking recipes, encyclopedia articles, newspaper columns, and diary entries, among other text works, may also fit on just one or a few pages of a book.

It should therefore be no surprise that photographers, illustrators, and other visual artists are among the signatories of the Appeal from the victims of CDL and the associated FAQ about CDL. Nor should it be any surprise that one of the first documented uses of the Internet Archive’s API has been to identify and selectively download all those scanned images of book pages that include illustrations, as shown in this example from an article on “Extracting Illustrated Pages for Digital Libraries“:

Each page image retrieved included an entire distinct graphic work. This example happens to be of pages from a book scanned by Google for the Hathi Trust rather than by the Internet Archive. But the posted code also includes libraries for accessing the Archive.org API and book page images with similar results.

Unlike direct downloading or viewing of page images from Archive.org by URL, using the Archive.org API to retrieve page images requires a username and password (which anyone can obtain for free using any e-mail address, including a temporary “throwaway” address.) But as with viewing of pages on Archive.org (and unlike on OpenLibrary.org), there doesn’t appear to be any documented limit on how many users of the API can simultaneously retrieve the same page images.

This doesn’t appear to fit the definition of CDL or satisfy the test for lawful “fair use” copying and “re-publication” of entire works. As with some of the Internet Archive’s other practices noted above, it’s unclear if this practice would be defended by supporters of CDL on some other basis, and if so, what that might be. So far was we can tell, it’s copyright infringement.

- Downloads via OpenLibrary.org of e-books assembled from page images

-

B. How are authors (and publishers) harmed by this?

- Brewster Kahle of the Internet Archive said again in a blog post and in a letter in response to Senate criticism last week that most of the uses being made of the Internet Archive’s scanned images of pages of books are of just one or a few pages from each book.

In his blog, Kahle talks only about the number of e-books “checked out” and “borrowed” by registered users. He says nothing about the much larger number of page views of images of books served up directly on the Web.

Kahle claims that, “The large number of books that have no activity beyond the first few minutes of interaction suggest patrons are using our service to browse books.” But he provides no basis for this assumption. It’s equally plausible (and seems to us to be more likely) that people are using Archive.org, as it was intended, to obtain the entirety of a passage, excerpt, illustration, or photo of interest–such as one of those cited by, and linked from, Wikipedia.org.

Kahle also says–again consistently with previous statements by the Internet Archive about the publication dates of the books that it has scanned–that 90% of the e-books “checked out” from the so-called “National Emergency Library” have been created from scans of books published more than 10 years ago. By that time, most books are out of print in the original editions, although many works included in “out of print” books are still (or once again) available in other editions or formats including as Web pages, paid downloads, etc.

The Internet Archive has never made any attempt to determine whether any of the works included in the books it scans are available in other formats. Like other librarians we have approached, the Internet Archive has ignored or rejected out of hand our requests to allow authors to add pointers to catalog listings on OpenLibrary.org or Archive.org (or other bibliographic databases) to allow readers to find existing authorized digital versions of works previously included in printed books.

The lesson Kahle appears to want us to draw from this data, and that some defenders of the Internet Archive seem to have drawn, is that because many of these books are no longer available for sale in the original book form, and because few “borrowers” of the Internet Archive’s bootleg e-books are reading entire books, there has been little harm to authors’ or publishers’ interest in book sales.

This may be largely true, but for works that aren’t currently available in any book form, it’s also largely irrelevant. Of course there’s no effect on the sales of the original books, if they are no longer available for sale in that format. And of course people aren’t likely to buy a copy of a book if all they want is an excerpt, photo, or illustration.

The real lesson though, is this: If these works are being distributed and read primarily as individual pages rather than as entire books or e-books, and most of them aren’t available in the original book formats, the only reason to talk about “book sales” is to set up a straw man that can easily be knocked down–and to distract attention from the real issues of clickstream diversion and undermining of revenues from digital rights.

Especially for distribution on the Web of images of individual pages, rather than downloads of e-books, it should be obvious that the relevant market is not primarily the market for books or e-books, but the market for distribution on the Web of digital copies of works included in books: text excerpts, illustrations, photos, etc.

If what people are actually reading and viewing are digital images of pages scanned from books, then the issue is the effect on the markets for the works that appear on those pages–which may or, in many and perhaps most cases, may not include book sales at all.

What are the normal modes of commercial exploitation of webpages containing works that have previously appeared in printed books?

Both defenders of “Controlled Digital Lending” and defenders of the “National Emergency Library” have been determined to avoid engaging with this issue. We sent copies of the joint Appeal to readers and librarians from the victims of CDL and FAQ on CDL a year ago to both the Internet Archive and the authors of the White Paper supporting CDL, but to date have received no response from any of them. Meanwhile, they have persisted in beating up the straw man of “impact on book sales,” despite the detailed taxonomies we have provided in our FAQ on CDL and in other presentations of the many other ways authors are monetizing written and graphic works in digital formats.

In an article published shortly after the release of our Appeal and FAQ on CDL, the lead authors of the White Paper on CDL doubled down on their straw-man argument about book sales, claiming categorically that, “With most 20th-century books—the books that we feel are the best candidates for CDL—the market to date has been exclusively print.” [Emphasis added.] Working authors know that this is nonsense.

Authorized Web pages through which works that have been included in printed books are available include authors’ own websites, other websites to which content has been licensed, websites for distributors of e-books and other paid downloads, and websites of stock photo licensing agencies, article syndication services, and other reproduction rights organizations (licensing agencies).

Page views can be monetized in many ways. Authorized sites can generate revenues from Web content–including content which has previously appeared in books–through advertising and through fees for downloads, subscriptions, and/or licensing. Many works that are available on these websites at no charge to the reader or viewer generate advertising revenues for the author.

On the Web, clicks are money. Clickstream diversion deprives legitimate sites of revenues even if the pirate site is operated by a nonprofit entity and distributes its bootleg copies for free.

Each visitor who views the image of a page of a scanned book on Archive.org, or though its API, or through OpenLibrary.org, doesn’t search for or visit any of the legitimate Web pages through which the same written and/or graphic content is available.

The passages from a writer’s work that are cited on Wikipedia.org, or that readers are searching for on Archive.org or OpenLibrary.org, may be her most valuable works. They are the excerpts that she is most likely to have made available in some authorized digital form. And the Web pages on which they can be found may be the most visited and highest revenue-generating pages of her personal website.

By diverting visitors to page images on Archive.org, the Internet Archive is skimming off some of the most potentially valuable traffic to legitimate websites from visitors and fans who might otherwise generate ad revenue, pay for short-form or long-form downloads or self-published e-book editions of out-of-print books, subscribe to the author’s newsletter or premium content, learn about her other works, or hire her for writing, speaking, or consulting.

These readers might also, of course, find and read the works they were looking for, perhaps in updated, enhanced, or more useful versions than they would find on (or be directed to by) the Internet Archive’s websites.

The minimum “lower bound” to the revenue diversion and damage to authors’ income from the Internet Archive’s distribution of Web pages with unauthorized images scanned from books is the number of such page views multiplied by the average value of each page view. Only the Internet Archive knows how many page views of book scans it has served up through its websites, “book reader” widgets, APIs, etc.

Some defenders of the Internet Archive continue to assume that authors who oppose CDL or the “National Emergency Library” are Luddites who don’t want our work online at all. But the truth is just the opposite. As we noted when the coalition FAQ and Appeal from the Victims of CDL were released, those authors who are most being harmed by, and who are objecting most strongly to, having our works scanned and given away in unauthorized (and typically inferior) digital formats by the Internet Archive are the most tech-savvy and entrepreneurial authors. We are the authors who are already doing the most to make our own personal backlists–including works included in books–available online.

Authors’ typically own a much larger share, vis-a-vis publishers, of rights to digital uses of their older personal backlists (50-100% depending on whether digital subsidiary rights were assigned to a print publisher and/or have reverted) than of revenues from traditional books (5-15% author royalty) or e-books (at most 25%). So revenues from digital rights to works included in older books are much more significant to authors than to the original publishers of those books. The different author-publisher revenue splits mean that typical publishers are focused on the next print bestseller, while authors are more likely to be focused on making the most of the digital rights to our personal backlists. Readers and librarians who want more of those backlist works to be available in digital formats should be supporting, not undermining, these authors’ efforts.

Online mail-order sales of printed books are unlikely to make up for the reduction in sales of printed books through bookstores that are closed during the pandemic. More people are reading online, however, and are searching online for reading material. Links from library catalogs to OpenLibrary.org rather than to authorized “e-lending”, and links to images of pages of books on Archive.org rather than to legitimate Web pages where these works can be found, are directly diverting some of the readers and Web traffic that would otherwise give authors some of their best chances to make up, at least in part, for the reduction in their incomes from book sales.

-

C. Can authors (or publishers) exclude their works from this scheme?

- The Internet Archive has said that authors who don’t want their books to be made available by the Internet Archive as part of the “National Emergency Library can “opt out” by sending a “removal request” to <info@archive.org> with “National Emergency Library Removal Request” as the subject line.

The Internet Archive has offered no guarantee that it will honor such requests, and has specified no “opt out” procedure for works in books it has scanned that are available through OpenLibrary.org and Archive.org but aren’t included in the “National Emergency Library”.

So far as we know, the Internet Archive and the authors of the White Paper and FAQ supporting CDL have ignored or refused all requests to meet or talk with individual authors, the NWU, or the signatories to the joint Appeal from the Victims of CDL for dialogue with librarians, despite recent claims to be “engaging in a dialog with authors.”

Unfortunately, the Internet Archive’s track record with respect to “opt-out” requests casts grave doubts on whether it can now be trusted to honor them.

The Internet Archive first began offering authors a way to opt out of some of its “re-publication” schemes in 2002, just a year after the Internet Archive launched its “Wayback Machine.” The Internet Archive posted the following statement on Archive.org:

Removing Documents from the Wayback Machine

The Internet Archive is not interested in offering access to Web sites or other Internet documents whose authors do not want their materials in the collection. To remove your site from the Wayback Machine, place a robots.txt file at the top level of your site (e.g. www.yourdomain.com/robots.txt) and then submit your site below.

The robots.txt file will do two things:

- It will remove all documents from your domain from the Wayback Machine.

- It will tell us not to crawl your site in the future.

To exclude the Internet Archive’s crawler (and remove documents from the Wayback Machine) while allowing all other robots to crawl your site, your robots.txt file should say:

User-agent: ia_archiver

Disallow: /Robots.txt is the most widely used method for controlling the behavior of automated robots on your site (all major robots, including those of Google, Alta Vista, etc. respect these exclusions). It can be used to block access to the whole domain, or any file or directory within….

Once you have put a robots.txt file up, submit your site (www.yourdomain.com) on the form on http://pages.alexa.com/help/webmasters/index.html#crawl_site

In 2011, the “once you have put a robots.txt file up, submit your site” line was removed from this page, suggesting that robots.txt directives alone could be used to block access. The “Removing Documents from the Wayback Machine” page on Archive.org remained up, with these instructions, until at least 2015.

The Internet Archive FAQ page spelled out what this was supposed to mean: “By placing a simple robots.txt file on your Web server, you can exclude your site from being crawled.” But that didn’t actually exclude sites from being crawled.

Authors and web publishers’ wishes couldn’t possibly have been expressed any more clearly, with respect to the Internet Archive’s crawling of specific sites or pages at specific times. But the Internet Archive never matched its deeds to its words, and never acted in accordance with the robots.txt norms and expectations it espoused.

Even when authors were able to put the line specified by the Internet Archive into a robots.txt file, in the format the Internet Archive had specified, and submitted their site on the form at “alexa.org” as also specified, the Internet Archive continued to crawl those sites.

For many years (we can’t tell how many), the Internet Archive crawled sites from which it was excluded by robots.txt directives, but did so quietly. It collected and retained copies of every page, but didn’t distribute them through its “Wayback Machine.” Most Web publishers didn’t scrutinize their server logs carefully enough to realize that the Internet Archive was ignoring the robots.txt directive and crawling their entire site. (The Internet Archive itself recommends against keeping sufficiently detailed logs to identity visitors.)

In 2017, the Internet Archive published a blog post, without fanfare, the next-to-last paragraph of which was, “A few months ago we stopped referring to robots.txt files on U.S. government and military web sites for both crawling and displaying web pages (though we respond to removal requests sent to info@archive.org). As we have moved towards broader access it has not caused problems, which we take as a good sign. We are now looking to do this more broadly.”

What did “more broadly” mean? There was no further explanation.

What had actually happened was that the Internet Archive had never honored any robots.txt directives not to crawl sites. Now it had started displaying complete (unauthorized) copies of newly-crawled sites that had carefully followed the Internet Archive’s exclusion instructions, and copies of all the version of these “opted-out” sites that its crawlers had been collecting for the previous years in contravention of robots.txt exclusion directives.

If authors or web publishers learned about the Internet Archive’s past disregard for robots.txt directives and its new practice of displaying those copies, they had to scramble to opt their sites and works out again. They had to follow a completely different email procedure, even though they had dutifully followed the Internet Archive’s own instructions for how to “exclude the Internet Archive’s crawler (and remove documents from the Wayback Machine).”

Why did the Internet Archive renege on its promises? It has ignored our requests to meet or talk with us about its actions. But to the extent that its blog post offered explanations, they made no sense.

The Internet Archive says that sometimes, when ownership of a domain name changes, a robots.txt file is added to the website of a previously crawled domain name. Apparently the Internet Archive had, on its own initiative, been suppressing display of copies of previously crawled sites whenever the current robots.txt file excluded it. Perhaps this was, in part, because it never respected robots.txt directives in crawling, but only partially in display of copies.

But that’s not how robots.txt was ever supposed to work, or how anyone had asked the Internet Archive to operate. Robots.txt directives were supposed to be directives not to crawl a site. If the site wasn’t crawled, the crawler would obtain no copies to display. A well-behaved robots is supposed to check for a robots.txt file in the root of each site before attempting to crawl a site, and follow its instructions for that crawl. Nothing in the robots.txt specifications ever said it was supposed to indicate anything about the display of copies that had been retrieved at a time when there was no such directive in place.

The Internet Archive also suggested that “the robots.txt files that are geared toward search engine crawlers do not necessarily serve our archival purposes.” Generic robot directives in robots.txt files might not have been intended to apply to the Internet Archive (although the robots.txt standard suggests that they would apply to all crawlers). But the directives in question were specifically directed to the Internet Archive, in the form the Internet Archive had specified.

It’s not as though the Internet Archive decided that it was entitled to ignore “No Trespassing” signs, on the grounds that it was special and maybe people didn’t mean those signs to apply to the Internet Archive. It’s much worse than that. The Internet Archive told authors, “If you put up a sign in exactly this location, in exactly this format, that says specifically, ‘No trespassing by the Internet Archive,’ we won’t come into your house.” People put up signs just like that, and thought they were safe. But the Internet Archive ignored those signs, walked past them into houses at regular intervals, took pictures of everything it could see, and–years later–put those pictures on the Internet.

When a commenter on the Internet Archive blog objected to the behavior of the “ia_archiver” crawler, the director of the Wayback Machine responded that, “The ‘ia_archiver’ User Agent is used by Alexa Internet, not the Internet Archive.” But that was the user agent most recently specified by the Internet Archive for exclusion from the Wayback Machine. Requests to the Internet Archive to specify the new user agent string(s) by which its crawlers are now identified, or the IP address range(s) they use, have been ignored. Those who want to exclude the Internet Archive’s crawlers are forced to resort to increasingly burdensome technical blocking measures.

The current terms of use for the Internet Archive say that, “sometimes authors and publishers express a desire for their documents not to be included in the Collections (by tagging a file for robot exclusion or by contacting us or the original crawler group). If the author or publisher of some part of the Archive does not want his or her work in our Collections, then we may remove that portion of the Collections without notice.”

This says only that the Internet Archive “may” remove such content, not that it will. And given that the Internet Archive no longer appears to pay any attention at all to robots.txt directives, it’s hard to see the mention of “robot exclusion” tags in these terms of use as other than an attempt to deceive authors and Web publishers who are still relying on the Internet Archive’s longstanding promises to honor robot exclusion directives.

With similar disingenuousness, a current Internet Archive help page for the Wayback Machine, most recently updated last year, says that, “It’s also possible that some sites were not archived because they were … blocked by robots.txt.” That certainly implies that the Internet Archive would treat a robots.txt exclusion directive as a “block.” But it doesn’t now, and it never did.

In light of this history, the Internet Archive has a long way to go to convince authors or publishers that we should trust what it now says–which is less than definite anyway–about what it will do if we ask to “opt out” of having books that include our works scanned or “re-published.”

If the Internet Archive and the authors of the White Paper on CDL want to show good faith, they need to engage with their critics.

Librarians, too, need to listen to, and engage with, authors. Librarians aren’t trying to harm authors. But they need to recognize that until they sit down (physically or virtually) with authors, they will have heard only one side of this debate. The voices of well-meaning librarians who consider themselves allies of authors, welcome though they are, are no substitute for giving impacted individuals–authors, in this case–a seat at the table to speak for ourselves when library policies that affect us are being considered. If we say, “Stop! You are hurting us,” it’s the height of condescension to respond by telling us that you know better than we do whether we are being harmed, or that what you are doing to us is really for our own good.

Please, librarians, can we talk?

NWU is the sole provider of IFJ Press Passes to freelance journalists in the U.S.

NWU is the sole provider of IFJ Press Passes to freelance journalists in the U.S.