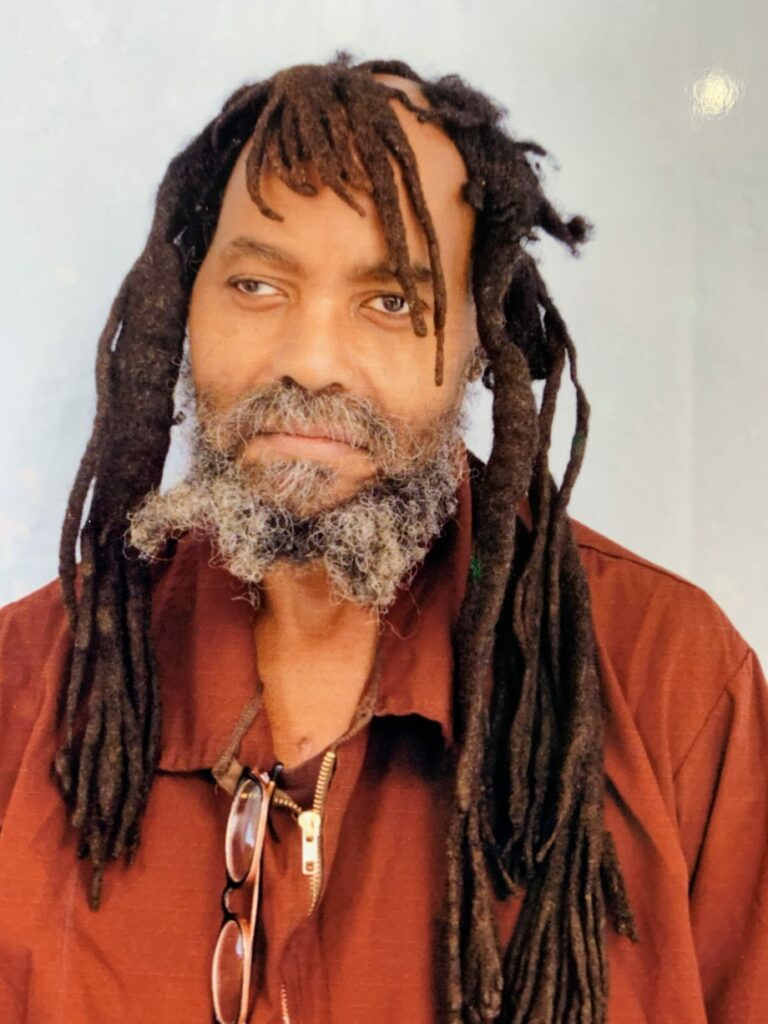

(NWU is proud to showcase this piece from NWU member Mumia Abu-Jamal in love and solidarity. We are excited to announce that this is the first of what will become a regular column for Mumia in the NWU newsletter. The struggle goes on, under any and all conditions.)

Many years ago, while working in public radio, I did a piece on a Senegalese historian named Al Hadji Bai Konte. Mr. Bai Konte was what Senegalese called a Griot, or one who orally records and remembers the histories of the nation, the glory of kings and tribal lore. He did so by song, with which he assisted by the playing of an instrument called a kora. The kora was a calabash to which a long neck was attached which made a high-toned sound like a high-pitched guitar.

The Griot, or singer of tribal histories, was taught as a youth to memorize the lineages of the kings, and how to play the kora. I did not understand Wolof, Al Hadji Bai Konte’s language, but if memory serves, he was accompanied by a translator. That was many years ago, but occasionally, I think of this exchange as a classic example of how Senegalese culture trained its historians to sing a song of yesteryear.

Many of us writers, whether we write for newspapers, magazines or websites, recall the old saying that our work is the first draft of history. We cover communities, not tribes. We cover presidents, governors and mayors, not kings. But few of us sing songs of our work. But we tell stories of the People; their struggles, their stumbles and their triumphs.

We tell stories of the people; and I like to think that we are griots still.

NWU is the sole provider of IFJ Press Passes to freelance journalists in the U.S.

NWU is the sole provider of IFJ Press Passes to freelance journalists in the U.S.