How will “generative artificial intelligence” affect writers and other media workers? To ask the question in this way almost seems to imply that we are passive objects of forces unleashed by venture capitalists and Internet platforms. But as a union, we don’t accept a role of passive victimhood.

Our goal is to use the power of collective action to assert our right to control our own working lives. That’s what it means to be a union. We’re interested not just in the impact of generative AI on writers and our incomes, but on what we can do together to have an impact on how it’s used and who profits from it.

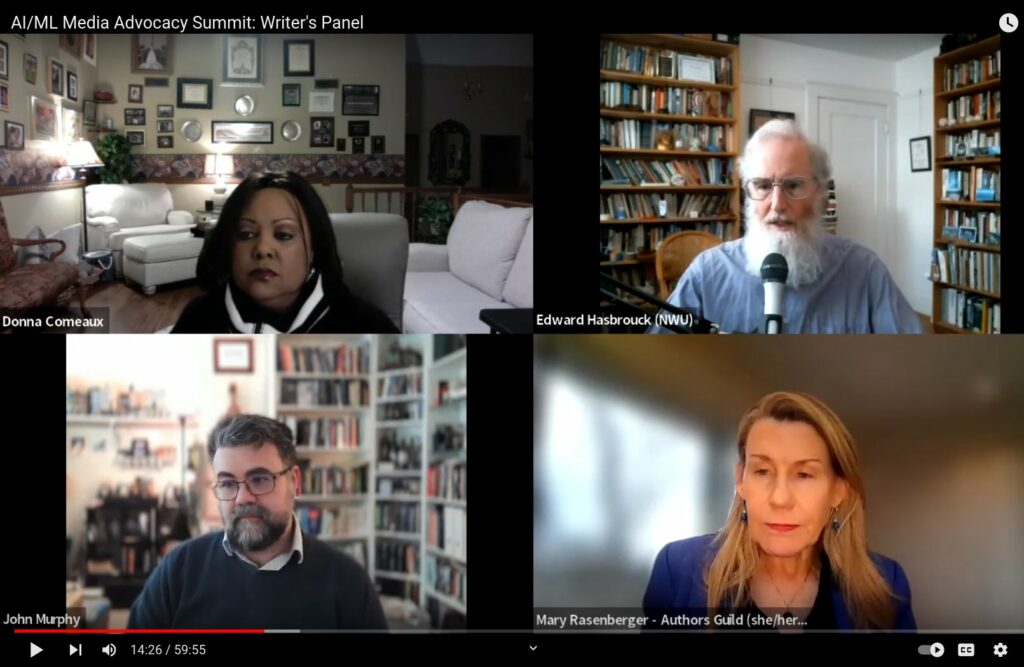

In this spirit of solidarity, the NWU joined with other media workers in a day-long mutidisciplinary Media Advocacy Summit on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning on March 10, 2023, “a free online event bringing together experts and creators to discuss the creative community’s response to AI/ML media generators.” Recordings of all of the sessions are available here. (Click the “Rewatch” links.)

Travel journalist, book author, professional blogger, and web content creator Edward Hasbrouck represented the NWU on the panel on writers and IA media generators, along with sci-fi author and machine learning expert John Murphy of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA), copyright attorney Mary Rasenberger of the Authors Guild, and moderator Donna Comeaux.

OpenAI has received a billion dollars in venture capital to develop ChatGPT. None of that money has been passed on to the creators of the works that have been used to “train” ChatGPT. Nor has OpenAI announced any plan to share with creators any of the billions of dollars in revenues its investors expect it to generate. The same is true for other generative AI systems. OpenAI has kept secret what’s in this “corpus” of training material. It’s likely to consist mostly of content scraped from the web, but it may also include content illegally scanned and copied from books.

Generative AI needs valuable training material as part of the input from which it generates valuable output. Without that training material and the prompts provided by users, generative AI would generate only garbage. It’s a fundamental principle: “Garbage in, garbage out.”

It’s an open question how much of the value of the output from ChatGPT or other generative AI systems is attributable to the training material, how much to the prompts, and how much to the AI software. But clearly the value contributed by the training material is more than zero, which is what creators have been paid to date. Even if the software has contributed as much to the value of the output as the training material, that would call for a 50/50 split of revenues.

Given that OpenAI alone has already received a billion dollars for the development of ChatGPT, but has paid nothing to the creators of the corpus of training material without which ChatGPT would be useless, those creators have already been deprived of hundreds of millions of dollars to which they are rightfully entitled.

How can we get our fair share of the gusher of revenue from generative AI? How can we make sure that writers and other digital media creators are treated fairly by providers and users of generative AI?

The NWU sees moral rights, collective licensing, and collective organizing as essential elements of our work for fair treatment and fair payment for creators of works used to train generative AI.

The moral rights of creators are recognized by international treaties ratified by, and binding on, the U.S. Moral rights are framed in international law as human rights of creators, not property rights, and are explicitly independent of intellectual property ownership.

That means that even if someone has the legal right to use your work without paying for it, they still have the legal duty to respect the moral rights of the creator(s) of that work. This applies even to copying or other use that is allowed without payment under U.S. law as “fair use”.

The Berne Convention on Copyright recognizes two moral rights which are significant with respect to generative AI:

Even if it’s legal to use our work, without remuneration, to train generative AI, we still have the “right to attribution”. This is the right to be identified as the authors of our works and of works created from ours. This would require disclosing that a work was created from a certain corpus of training material and identifying what’s in that corpus.

We also have the “right to integrity”. This is the right to object to distortion, mutilation, or any other use of our work prejudicial to our reputation. This would allow us, for example, to object to the use of our works as the basis for fascist propaganda, fake news, defamatory material, or spam.

Despite what the name might suggest, the “moral rights” of authors aren’t just a moral issue but a legal one. Many other laws, after all, are designed to provide legal protection for other sorts of human and moral rights, including those recognized by international treaties. That’s part of what laws are for.

The problem is that although the U.S. has ratified international treaties that give the moral rights of authors the same Constitutional status (“the supreme law of the land”) as the First Amendment, Congress has done nothing to fulfill its treaty obligation to make the moral rights of writers enforceable under U.S. law. It has enacted partial protections (although they are still inadequate) for some of the moral rights of visual artists, but none at all for writers.

The U.S. Copyright Office did a study of the moral rights of writers a few years ago, but despite appeals from the NWU and our U.S. and international allies, it recommended that Congress continue to do nothing.

Moral rights legislation for writers isn’t a magic bullet for misuse of generative AI, but it would provide a way of reining in some of its worst problems, and a framework to build on in addressing others. Writers and readers who care about writers’ rights should insist that moral rights legislation be included as an essential part of any copyright law package to address the issues with generative AI.

We’ll be renewing our call for legislation to create a right of action for violations of writers’ moral rights at the U.S. Copyright Office listening session on writers and artificial intelligence on April 19, 2023.

As for economic rights, payments to authors of works used to train generative AI will almost certainly require collective licensing.

The NWU has been critical of collective licensing schemes that impose de facto compulsory licenses when individual licensing would be feasible. Creators might not want to grant any license, or might already be monetizing their own works in ways they prefer.

Generative AI is different. A generative AI product like ChatGPT, which has been trained on a corpus of millions of works, seems to be the exceptional case in which only collective licensing is feasible. This would mean a collective licensing organization negotiating a license on behalf of all contributors to the corpus, collecting a fee for its use, and then distributing the fee to those contributors. Arbitration before a government rate-setting body might be an alternative to negotiations, and is used for some statutory music licenses, but these don’t seem to have worked well for musicians.

The NWU has been an active member and has been represented on the Board of Directors of IFRRO, the international federation of collective licensing agencies. Generative AI is already under discussion at IFFRO. We will continue to work with other organizations of creators and IFRRO members toward a collective licensing framework for works used to train generative AI.

As in union organizing, the prerequisite to collective bargaining over the rates and terms of a collective licensing agreement is an organization sufficiently representative of the creators of the works being licensed. In the case of generative AI, that would start with creators of web content that is being scraped and ingested for training. The NWU is one of the few organizations whose membership includes significant numbers of web content creators. The greatest growth in the NWU’s membership in recent years has been in our digital media workers division, the Freelance Solidarity Project.

Most digital content creators are not yet members of the NWU or any organization of creative workers. And it would be easier to organize ourselves if the right of freelancers and self-publishers to organize and act collectively as workers were clarified by Congress. This, too, should be part of any legislative package to address the issue of generative AI. We should not have to fear that we will be accused of violating antitrust laws if we seek to exercise our rights as writers and digital media workers, such as by organizing and negotiating collectively with generative AI providers.

The bottom line is that if we want to get our far share of the generative AI bonanza, we need to organize more creators of web and other digital content. Only then will we be in a position to negotiate a collective licensing agreement on behalf of the creators of works used to train generative AI. We need to help other digital media workers understand how much potential income for them could be at stake through generative AI, and how much has already been stolen from them.

The potential opportunity to participate in collective licensing for generative AI use may be what it takes to get creators to band together. If you want your fair share, we invite you to join us!

NWU is the sole provider of IFJ Press Passes to freelance journalists in the U.S.

NWU is the sole provider of IFJ Press Passes to freelance journalists in the U.S.